Mounted Troops in the Era of Mechanised War

The most surprising thing about Web Equipment, Cavalry Pattern 1940 is that it exists at all. Sir Basil Liddell Hart's revolutionary theories of mechanised warfare first appeared in 1925, and his most apt pupil, Panzer General Heinz Guderian, had demonstrated their efficacy to all of Europe in 1939. In a world of blitzkreig, horse mounted cavalry seemed little more than a quaint anachronism. It must be noted, though, that from today's perspective it is easy to forget that the military technology of 1940 was much closer to the trenches of 1918 than to the modern machinery of war. The first all-wheel-drive light military vehicle, the American Jeep, was still just a prototype in 1940. The British Army, faced with the need for mobile patrols deep into the deserts of the Middle East, fell back on the tried-and-true: a man on a horse. The Cavalry Equipment still on the books was the venerable Bandolier Equipment, Pattern 1903. This pattern had served the Army well in the first war, although its well known limitations almost led to its being replaced in 1914. Only the outbreak of hostilities kept it on the books then, and twenty-six years on the need for a replacement seemed clear.

The most surprising thing about Web Equipment, Cavalry Pattern 1940 is that it exists at all. Sir Basil Liddell Hart's revolutionary theories of mechanised warfare first appeared in 1925, and his most apt pupil, Panzer General Heinz Guderian, had demonstrated their efficacy to all of Europe in 1939. In a world of blitzkreig, horse mounted cavalry seemed little more than a quaint anachronism. It must be noted, though, that from today's perspective it is easy to forget that the military technology of 1940 was much closer to the trenches of 1918 than to the modern machinery of war. The first all-wheel-drive light military vehicle, the American Jeep, was still just a prototype in 1940. The British Army, faced with the need for mobile patrols deep into the deserts of the Middle East, fell back on the tried-and-true: a man on a horse. The Cavalry Equipment still on the books was the venerable Bandolier Equipment, Pattern 1903. This pattern had served the Army well in the first war, although its well known limitations almost led to its being replaced in 1914. Only the outbreak of hostilities kept it on the books then, and twenty-six years on the need for a replacement seemed clear.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement, signed during the Great War, carved-up the Middle East, with reverberations that are still with us today. It provided for several Mandates, France was to oversee affairs in Syria, whilst Great Britain had two Mandates, in Palestine and the Trans-Jordan, the territories which today are Jordan and Iraq, then called ‘Irak, as it was Al Irak in full. In 1939, two horsed regiments of cavalry, Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons) and the Royal Dragoons (1st Dragoons) were already stationed in Palestine, on what were called “policing duties”. The collapse of France saw Vichy France, under Gen. Petain, throwing in its lot with Nazi Germany. Syria then aligned itself with Vichy France.

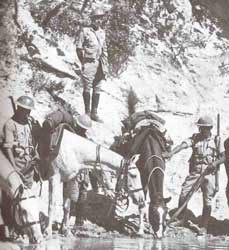

Faced with the enemy, literally on their doorstep, the War Office decided to form a 1st Cavalry Division to augment the two mounted regiments already in Palestine.Between the Wars, a steady process of mechanisation had seen many Yeomanry regiments converted to searchlight, light anti-aircraft, or armoured car regiments. However, not all Yeomanry regiments were yet converted and still had horses. Accordingly, eight regiments were transferred to the new 1st (Cavalry) Division, together with a Regular Army unit, the Household Cavalry Regiment. This was drawn from the 1st and 2nd Life Guards and the Royal Horse Guards, who retain their horses to this day. The photo below shows a horse unit with members of the Trans Jordan Frontier Force in Palestine. This photograph is provided courtesy of Sam Cox and The Society of the Military Horse.

Just to obtain sufficient horses was a logistical nightmare, let alone finding sufficient soldiers with the necessary skills, e.g. farriers and saddlers, together with personnel experienced in handling horses.. In September 1939 – the first month of the War - 9,000 remounts were purchased, with few remount officers available to oversee the task. These were transported in February 1940, across the Mediterranean Sea, with losses of only 1.6% that died or had to be destroyed. The already hard-pressed Remount and Veterinary Services had to care for 722 horses. 1. The logistical problems also included accoutrements and this caused the War Office to approach the Mills Equipment Company. It is not recorded whether there were still any W.O. staff who recalled the pre-1914 Cavalry Equipment Trials

Just to obtain sufficient horses was a logistical nightmare, let alone finding sufficient soldiers with the necessary skills, e.g. farriers and saddlers, together with personnel experienced in handling horses.. In September 1939 – the first month of the War - 9,000 remounts were purchased, with few remount officers available to oversee the task. These were transported in February 1940, across the Mediterranean Sea, with losses of only 1.6% that died or had to be destroyed. The already hard-pressed Remount and Veterinary Services had to care for 722 horses. 1. The logistical problems also included accoutrements and this caused the War Office to approach the Mills Equipment Company. It is not recorded whether there were still any W.O. staff who recalled the pre-1914 Cavalry Equipment Trials

The Mills Equipment Company was more than willing to provide a solution to the problem. M.E. Co.'s Chief Designer, Albert Lethern, had received his first patent for a Cavalry Equipment in 1911. It was a modification of this equipment that General Sir John French recommended for adoption, and which was stillborn by the advent of the First War. Mills, and Lethern, never gave up on the Cavalry Equipment, a variation of the pattern being adopted by Spain. The history of its development from 1911 until 1940 is fascinating, convoluted, and in many details still unclear. This subject is addressed in greater detail below in "A Short History of Mills Cavalry Web Equipment". Suffice it to say M.E. Co. proposed, and the War Office adopted, what was to become Web Equipment, Cavalry, Patt. '40. Photographs show that the 1st Cavalry Division continued using Patt. ’03 B.E., and most examples of W.E. Patt. '40 are found in mint, un-issued condition.

The decision to form the 1st Cavalry decision had been taken before Winston Churchill became the Prime Minister. He quickly made his objections known, on what he regarded as a waste of men and materiel:-

P.M. to Gen. Ismay 12 Aug 1940 “…A proposal should be made to liberate immediately a large portion of the garrison, including the Yeomanry Cavalry Division…” 2

(Action this day) P.M. to Secretary of State for War and C.I.G.S. 8 Sep 1940 “…It has been heartbreaking to me to watch these splendid units fooled away for a whole year. The sooner they form machine-gun battalions, which can subsequently be converted into motor battalions, and finally into armoured units, the better. Please let nothing stand in the way. It is an insult to the Scots Greys and Household Cavalry to tether them to horses at the present time. There might be something to be said for a few battalions of infantry or cavalrymen mounted on ponies for the rocky hills of Palestine, but these historic Regular regiments have a right to play a man’s part in this war…” 3

P.M. to Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs 11 Jan 1941 “…The mechanisation of the Cavalry Division in Palestine is a distressing story. These troops have been carried out with their horses and maintained at great expense in the Middle East since the early months of the war. Several months ago it was decided by the War Office that they should be mechanised. I gladly approved. Now I learn…that nothing has been done about this, that the whole division is to be carted back home again – presumably without their horses. 4 – and that this is not to begin until June 1. After that there will be a further seven or eight months before they will be of any use. Thus 8,500 officers and men, including some of our finest Regular and Yeomanry regiments, will, except for security work, have been kept out of action at immense expense for two years and five months of war…”5

Churchill went on to demand the total costs of having transported the troops and horses there and now back, plus maintaining them (rations, pay, etc,) from September 1939 to the start of March 1942. He also compared the conversion of the Household Cavalry, during the latter part of the Great War, into a machine-gun regiment, plus suggested that training could instead be done in Palestine, where they might be turned into infantry battalions, or switched with Regular troops then in India. His point was that the personnel should not be returned to the U.K., when there was a greater need for men in the Middle East 6

Churchill went on to demand the total costs of having transported the troops and horses there and now back, plus maintaining them (rations, pay, etc,) from September 1939 to the start of March 1942. He also compared the conversion of the Household Cavalry, during the latter part of the Great War, into a machine-gun regiment, plus suggested that training could instead be done in Palestine, where they might be turned into infantry battalions, or switched with Regular troops then in India. His point was that the personnel should not be returned to the U.K., when there was a greater need for men in the Middle East 6

Having lost out in 1914, Mills had got their orders in 1939, but now there was a rather more formidable opponent to the continuance of production! In the event, Rashid Ali’s revolt in Iraq and the Siege of Habbaniya also intervened, some of the Yeomanry being converted to Lorried Infantry, as part of “Habforce”. The photo at left shows a Yeomanry Unit of 1st Cavalry in Palestine 1940.

The demise of the 1st Cavalry Division was certainly not the end of horses in the Second World War. By October, 1942, Tylden details 2,800 horses and mules in horsed transport companies, that usefully augmented M.T.. Six Cypriot pack transport companies were also in the Middle East, together with fifteen Indian mule companies and a mountain artillery patrol. In total there were over 6,500 horses, 9,600 mules, not forgetting 1,700 camels!7. 1st Army had two pack transport companies in N. Africa and, whilst most of the campaign utilised M.T., these pack companies came into their own in Sicily and Italy. During the latter campaign, pack transport was urgently required, 4,500 animals were to be shipped from M.E. H.Q., even accepting a swap - by reducing M.T. requirements by 1,000 vehicles. By 1945, there were over 1,000 horses and 11,754 mules with Field Units and a further 500 horses and 8,850 mules with the Veterinary and Remount services.8

With this amount of horsed transport and, presumably, their handlers, Patt. ’40 W.E. could well have  seen further use. However, photos of Patt. ’40 actually in use are not commonly encountered. The picture at right, shows troops of the Northern Indian Cavalry at Imphal, 1942. It was taken from larger picture published in Janusz Piekalkiewicz's The Cavalry of World War II.9 The two photos left below are from the same source. They show troopers of the Trans-Jordan Frontier Force. The one at far left was taken in Syria, Summer 1941, while the one near left, also from 1941, shows troops watering their horses in the Jordan River, Palestine. In the first picture, take a close look at the trooper in the middle. He has his braces on backwards! In the second picture, notice the officer standing high on the bank. He is wearing the Officer's set of W.E. Patt. '40. 10

seen further use. However, photos of Patt. ’40 actually in use are not commonly encountered. The picture at right, shows troops of the Northern Indian Cavalry at Imphal, 1942. It was taken from larger picture published in Janusz Piekalkiewicz's The Cavalry of World War II.9 The two photos left below are from the same source. They show troopers of the Trans-Jordan Frontier Force. The one at far left was taken in Syria, Summer 1941, while the one near left, also from 1941, shows troops watering their horses in the Jordan River, Palestine. In the first picture, take a close look at the trooper in the middle. He has his braces on backwards! In the second picture, notice the officer standing high on the bank. He is wearing the Officer's set of W.E. Patt. '40. 10

The addition of Basic pouches to Patt. ’40, in 1944, seems strange, but viewed in the light of what unknowns might have lain ahead, it may make more sense. Patt. ’40 catered only to users of the S.M.L.E., but the developing campaigns in Europe could well have required the use of mounted troops, dependent on the theatre. Machine Carbines would have been a useful, even normal, addition to the horsed soldier’s weapons.

The addition of Basic pouches to Patt. ’40, in 1944, seems strange, but viewed in the light of what unknowns might have lain ahead, it may make more sense. Patt. ’40 catered only to users of the S.M.L.E., but the developing campaigns in Europe could well have required the use of mounted troops, dependent on the theatre. Machine Carbines would have been a useful, even normal, addition to the horsed soldier’s weapons.

Post-war, horses and mules continued in service with the British Army, though on a far smaller scale. Seeing service in Cyprus, Hong Kong and elsewhere from the 50s to 70s, the most recent and surprising use was with British troops in the Kosova / Former Yugoslavia etc theatre, using locally procured horses. This was more practical than tactical, but the sight of D.P.M. wearing soldiers, in P.L.C.E. ’90 was an interesting sight! The potential necessity for a cavalry W.E. meant that W.E., Cavalry, Pattern '40 survived to appear in the Catalogue of Clothing and Necessaries, Section CN, in 1965.

When one examines W.E., Patt. '40, a Back-Adjustment Equipment in Mills terminology, its origins in W.E. Patts. ’13, ’19 and '25 are obvious. The prime difference lies in just two straps that speak of its cavalry lineage. These are the two horizontal straps, which extend rearwards from the top pocket of the Cartridge carriers. These support one side of the Haversack and Water bottle carrier across the wearer’s back and above his waist. The other support is by means of Sliding straps fitted with keyways, that pass over the Braces, through loops. The Keyways have “keyhole” shaped slots that mate to special studs on the brace buckles of the Cartridge carriers. When un-fastened from the studs, the Haversack and Water bottle carrier fall back and can then be accessed whilst in the saddle. All of these design elements are to be found again and again in the Mills Equipment Company's successive Cavalry Web Equipments.

Footnotes

- Tylden, Major G. Horses and Saddlery. J. A. Allen & Co., with Army Museums Ogilby Trust, 1980, p. 82 – 83

- Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War: Vol. II Their Finest Hour. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston, 1949, p. 426

- Ibid. p. 667

- Tylden, op. cit. p. 84. After 1918, the treatment of the Army’s horses, disposed of in the Middle East and maltreated and often worked to death by the local population, caused a scandal in the U.K.. The Brooke Hospital was later formed in Cairo, to give free treatment to these animals and continues to do so today. When the 1st Cavalry Division was disbanded, those horses not suitable for draught work were destroyed.

- Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War: Vol. III The Grand Alliance. Cassell & Co. Ltd. 1950, p. 639 – 640

- Ibid. p. 639 - 640

- Tylden, op. cit. p. 84

- Ibid. p. 85

- Piekalkiewicz, Janusz. The Cavalry of World War II. Historical Times Inc., Harrisburg, Pa., 1987. p. 110

- Ibid. p. 115