General Sir Samuel James BROWNE, V.C., G.C.B., K.C.S.I.: A Short Biography

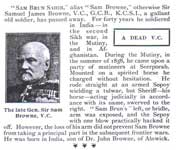

There seems to be some doubt as to where Sam Browne was born. His obituary in The Times has it as Alnwick, Northumberland, whereas Black & White Budget, the weekly magazine (below right), states it was in India, at Barrackpore. Either way, it was in 1824, as the son of a doctor, who did come from Alnwick. He joined the 46th Bengal Native Infantry in 1840, seeing action at Ramnuggar, Sadoolapore, Chillianwallah and Gujerat during the Second Sikh War, 1848-9.After the war, five regiments of Sikh cavalry were raised and Sam was directed to form the second of these, though he was not the Commanding Officer. Later, he was listed as being in command of the both 2nd Punjab Irregular Cavalry and the Corps of Guides, from 1850 to 1869. During this period, he and the regiment saw much action on the North-West Frontier. The photo of Sir Samuel at left is from an 1897 issue of The Navy & Army Illustrated magazine.

There seems to be some doubt as to where Sam Browne was born. His obituary in The Times has it as Alnwick, Northumberland, whereas Black & White Budget, the weekly magazine (below right), states it was in India, at Barrackpore. Either way, it was in 1824, as the son of a doctor, who did come from Alnwick. He joined the 46th Bengal Native Infantry in 1840, seeing action at Ramnuggar, Sadoolapore, Chillianwallah and Gujerat during the Second Sikh War, 1848-9.After the war, five regiments of Sikh cavalry were raised and Sam was directed to form the second of these, though he was not the Commanding Officer. Later, he was listed as being in command of the both 2nd Punjab Irregular Cavalry and the Corps of Guides, from 1850 to 1869. During this period, he and the regiment saw much action on the North-West Frontier. The photo of Sir Samuel at left is from an 1897 issue of The Navy & Army Illustrated magazine.

With over a decade of experience under his belt (no pun intended), he was evidently already in the process of a re-think on the way he could carry his sword and pistol. At that time two methods of carrying swords existed in parallel. The older system, dating back centuries, was the baldric, or cross-belt, with a belt plate for adjustment. In the latter part of the 18th Century, cavalry had begun to wear a narrow sword belt, with slings, one short and one long, to attach to the sword scabbard. When mounted the cavalryman’s sword hung at the side of his horse, presenting no encumbrance. However, when dismounted, the sword would drag on the ground. Next to the front (short) carriage, a hook was provided, onto which was slipped the top scabbard ring, thus lifting the sword clear of the ground. Infantry officers are shown wearing both forms from quite early in the 19th Century and from there on. Pistols, if carried, would require the eitherthe addition of a waist-belt or might be carried on another sling. It is not known which Sam first encountered as an infantryman, but now as a cavalryman he must have been familiar with the sword belt and slings. He evidently was not satisfied, as both were obviously less than efficient arrangements, when fighting dismounted actions.

In1852 the 14th Earl of Derby briefly became Prime Minister. In the same year, probably after his term of office ended, he was on a tour of the North-West Frontier. His escort was Sam Browne, who was still only a substantive Lieutenant, though he was ranked locally as a Lt. Colonel. Derby remarked on the number of weapons Sam was carrying and he replied that “…he was designing a new belt for his regiment and was finding out by practical experience the best way of carrying his arms...”. Elsewhere it is recorded that Sam’s belt was made up from bits of horse and harness, perhaps by his regimental saddler. This must have served as the prototype, as in 1856 Sam had brought a pattern from India, from which Mr. R. Garden, a saddler at 200, Piccadilly, London made up a “productionised” belt. The following year he was promoted to Captain.

In 1858 the Indian Mutiny broke out and the 2nd Punjab Cavalry were again in action. In July of that year, Sam received his brevetcy to Major, after action at Lucknow, with further action at Koorsee, Rooyah, Allygunge and at the capture of Bareilly. He now commanded a complete Field Force of cavalry and infantry at the Mohunpore action. At Seerporah, Sam and a single sowar charged a sepoy cannon that was threatening the line of approach. He charged at a rebel who was armed with a tulwar, but his horse “Sheriff” swerved to the right, exposing his bridle, or left arm, allowing the sepoy to virtually sever Sam’s left arm at the shoulder. He also sustained a severe sword cut to his left knee. At the conclusion of the Mutiny, Sam received a number of Mentions in Dispatches and the official thanks of both the Commander-in-Chief and Government. To this was added an appointment as Commander of the Order of the Bath (C.B.). He was promoted Brevet Lt. Col. in February 1861. The following month, for preventing the gun being brought into action at Seerporah, Sam was gazetted for the Victoria Cross. It is the loss of his left arm, the arm used to carry the sword whilst walking, that has led to the apocryphal story that he then invented his belt. As can now be seen, his design had merely been fortuitous. A photograph, taken in about 1861, shows him one-armed and bearded, still using a sword belt with slings and wearing his V.C., with Punjab, Mutiny and Indian General Service Medals.

Clearly, Sam’s new design soon caught on with his officers, since in 1859 an English officer in Sam’s 2nd Punjab Cavalry is shown wearing a form of “Sam Browne” belt. No brace is being worn, but the sword is very definitely in a “Sam Browne” style of frog and not on slings. News of this new design, a vast improvement on the existing system, eventually came to the attention of other officers serving in India, both in the Indian and British Armies. The system of “private purchase” allowed officers a wide latitude for tweaking what could only then be termed the “Sam Browne System”. They had their own versions made up, the word “version” being used advisedly.

Although still only a Captain, he had successively held the Brevet ranks of Major and Lt. Colonel, being confirmed as a substantive Major only in 1861. A further brevetcy to Colonel followed in 1864, followed by substantive Lt. Colonel in 1866. The term brevet requires some explanation. An officer could hold several ranks simultaneously. Firstly the substantive rank, for which the officer was paid and also a higher brevet rank, which was an acknowledgement of some exceptional service, but which was unpaid! Quite often an even higher, but “local” rank was held in addition to the substantive and brevet ranks. As commander of the 2nd Punjab Cavalry, Sam already held the local rank of Lt. Colonel, though still only a Captain. Now part of the Bengal Staff Corps, he was promoted to Major General in 1870. Sam was selected to represent the Anglo-Indian Army during the 1875 visit by the Prince of Wales, being rewarded with an appointment as Knight Commander of the Star of India (K.C.S.I.). Promoted in 1877 to Lieutenant General, he assumed command of the Lahore Division in the following year.

With the Crimean War at an end, Russia was able to turn its attention elsewhere. The threat of a Russian incursion into Afghanistan, was ever-present, requiring that Britain kept the Afghan ruler, Sher Ali, on-side. A British mission to Kabul had already been refused by Sher Ali, whose policy was to side with neither Britain nor Russia. Earlier political settlements had agreed that Afghanistan was in Britain’s sphere of influence, with neighbouring Bokhara in the Russian’s. Despite this, in 1878, a Russian mission arrived, uninvited, in Kabul. For Sher Ali, this was unwelcome, to say the least. The Governor-General, Lord Lytton, was understandably most put out by the presence of the Russians. He now gave an ultimatum to receive a British mission, but this expired and three columns of troops then advanced to open the Second Afghan War. Lt. General Browne, V.C. was appointed to command the Peshawur Valley Field Force, with Maj.-Gen. Frederick Sleigh “Bobs” Roberts, V.C. and Lt.-Gen. Donald Stewart respectively commanding the Kurram Valley and Kandahar Field Forces.

The Peshawur Field Force were to advance along the northernmost line from Peshawur, through the Khyber Pass and on to Jalalabad. At the Afghan end of the Pass stood the Fort of Ali Masjid, 500 feet up a hill, with fortifications on either side. The fort was held by Afghan regulars, with artillery support and with Afghan tribesmen dispersed on both flanks of the line of advance. Sam divided his forces, sending the 2nd Brigade around the flank to cut off the enemy’s line of retreat. The 1st Brigade attacked one flank, with the 3rd Brigade advancing on a frontal assault. The fort was stormed, without success, but learning of Sam’s encircling move, the Afghans retreated back up the Pass. Here they ran into the 2nd Brigade, lying in wait, who captured most of them. The line of advance was now cleared and ultimately all three Field Forces occupied Afghanistan. The war was not yet over, but space precludes a fuller account. Suffice it to say that “Bobs” Roberts, a fellow Mutiny V.C., added considerably to his reputation and eventually took the title of Earl Roberts of Kandahar. After the War, Sam received the thanks of the Government of India and of both Houses of Parliament and was raised to Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (K.C.B.) and added the Afghan Medal to his awards. The illustration at left, originally published in The Illustrated London News, 14 December 1879, shows Sir Samuel as a Lieutenant-General .

The Peshawur Field Force were to advance along the northernmost line from Peshawur, through the Khyber Pass and on to Jalalabad. At the Afghan end of the Pass stood the Fort of Ali Masjid, 500 feet up a hill, with fortifications on either side. The fort was held by Afghan regulars, with artillery support and with Afghan tribesmen dispersed on both flanks of the line of advance. Sam divided his forces, sending the 2nd Brigade around the flank to cut off the enemy’s line of retreat. The 1st Brigade attacked one flank, with the 3rd Brigade advancing on a frontal assault. The fort was stormed, without success, but learning of Sam’s encircling move, the Afghans retreated back up the Pass. Here they ran into the 2nd Brigade, lying in wait, who captured most of them. The line of advance was now cleared and ultimately all three Field Forces occupied Afghanistan. The war was not yet over, but space precludes a fuller account. Suffice it to say that “Bobs” Roberts, a fellow Mutiny V.C., added considerably to his reputation and eventually took the title of Earl Roberts of Kandahar. After the War, Sam received the thanks of the Government of India and of both Houses of Parliament and was raised to Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (K.C.B.) and added the Afghan Medal to his awards. The illustration at left, originally published in The Illustrated London News, 14 December 1879, shows Sir Samuel as a Lieutenant-General .

He retired as General Sir Samuel James Browne, V.C., G.C.B., K.C.S.I. and with a clutch of campaign medals and clasps. With his family, he took up residence in Ryde, on the Isle of Wight. His extensive contacts would no doubt have informed him that his Belt had been recommended for universal issue within the Indian Army in 1882. The equipment was evidently in wide use on Foreign Service and the 1897 edition of the Field Service Manual lists the complete “Sam Browne” equipment for sword, pistol and ammunition. An 1898 Army Order officially authorised the “Sam Browne” belt for Home Service, though it was necessary for Sam to point out that the holster design did not follow his specification, so it required modification! The Dress Regulations of 1900 contained a photographic plate showing the equipment, together with a text section describing the equipment. It was also announced in List of Changes, as Warrant Officers would also wear the new pattern. Sam died in 1901, in the same year as the Sovereign he had served for over 40 years. He was buried in Ryde. He therefore was not to see just how widespread the use of his design was to become. Officers of the Allied countries in 1914-18 wore the belt widely though, as a specifically field equipment in the British Army, it fell into disuse in this same period.

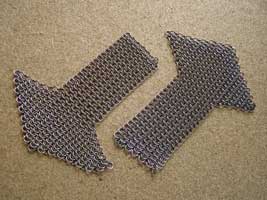

As a footnote, one further survival requires mention. Writing after the Mutiny, Sir Dighton Probyn, V.C. noted that officers of the 2nd Punjab Cavalry had sewn lengths of bridle curb chain across their shoulders. Plainly the lesson of what had happened to their C.O. had not been lost on them! This makeshift arrangement ultimately evolved into sections of chain mail, hooked over the shoulders, in place of cloth epaulettes. Officially termed Shoulder Chains, they were of epaulette width and, mimicking the tunic lace of old, were of “bastion” form. Shoulder titles and rank badges were then affixed directly to the chain mail. The photo far left shows a pair of regulation Shoulder chains. Near left, these are ganged curb chains, of the form posibly used by Sam Browne's Regiment, although no record exists of whether they used one, two, three, or four... Both photos from Shoulder chains in the John Tremelling Collection, photos © John Tremelling 2009. British cavalry regiments and the Royal Horse Artillery soon followed suit and later still the Yeomanry. In 1898 sealed patterns of both blue and red Frocks were authorised for cavalry, appearing in the 1900 Dress Regulations and these all had shoulder chains. Today, the “Sam Browne” belt is still in service, whilst cavalry and yeomanry still wear shoulder chains. Various elements of the Army, had worn a sword belt under the tunic, the gold laced slings being the only visible part. The 1900 Dress Regulations specified a web belt (actually canvas, rather than “web”. See Dress Regulations, 1900, para. 28 and Appendix VIII, (2)) for this purpose. It was furnished with metal loops on leather chapes for the slings and the sabretache. In addition to these, there was a pair of loops for a diagonal shoulder brace. The resemblance to a “Sam Browne” is so obvious, that it would seem to have been inspired by it.

As a footnote, one further survival requires mention. Writing after the Mutiny, Sir Dighton Probyn, V.C. noted that officers of the 2nd Punjab Cavalry had sewn lengths of bridle curb chain across their shoulders. Plainly the lesson of what had happened to their C.O. had not been lost on them! This makeshift arrangement ultimately evolved into sections of chain mail, hooked over the shoulders, in place of cloth epaulettes. Officially termed Shoulder Chains, they were of epaulette width and, mimicking the tunic lace of old, were of “bastion” form. Shoulder titles and rank badges were then affixed directly to the chain mail. The photo far left shows a pair of regulation Shoulder chains. Near left, these are ganged curb chains, of the form posibly used by Sam Browne's Regiment, although no record exists of whether they used one, two, three, or four... Both photos from Shoulder chains in the John Tremelling Collection, photos © John Tremelling 2009. British cavalry regiments and the Royal Horse Artillery soon followed suit and later still the Yeomanry. In 1898 sealed patterns of both blue and red Frocks were authorised for cavalry, appearing in the 1900 Dress Regulations and these all had shoulder chains. Today, the “Sam Browne” belt is still in service, whilst cavalry and yeomanry still wear shoulder chains. Various elements of the Army, had worn a sword belt under the tunic, the gold laced slings being the only visible part. The 1900 Dress Regulations specified a web belt (actually canvas, rather than “web”. See Dress Regulations, 1900, para. 28 and Appendix VIII, (2)) for this purpose. It was furnished with metal loops on leather chapes for the slings and the sabretache. In addition to these, there was a pair of loops for a diagonal shoulder brace. The resemblance to a “Sam Browne” is so obvious, that it would seem to have been inspired by it.

© R.J. Dennis February 2009